My Mistress's Sparrow is Dead

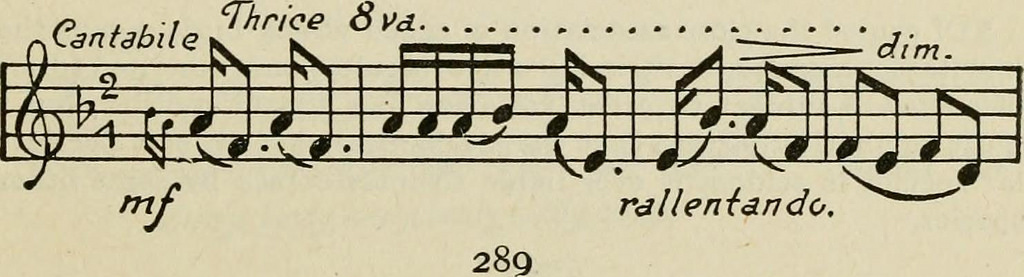

Musical notation of the song of the sparrow

I bought this book with the money from my first book review for the soon-to-be-deceased print edition of The Independent on Sunday. The novel I had reviewed, a Young Adult book called Red Ink by debut novelist Julie Mayhew, was beautiful – the story of a young girl’s journey of discovery from the outskirts of London to the heady melon fields of a Greek Island. The hard clean pre-release copy was a reward in itself, but I was keen to spend at least part of my fee on something which would last. A companion for the book which I had reviewed, so it wouldn’t feel so lonely – part of its own story with no friend to share its tale. I also hated knowing that much of this glorious money which felt somehow special would soon be swallowed up in rent, bills, food and bus fares. I gave myself permission to buy one beautiful new book with some of the fee. The rest – well, the prosaic details of life needed paying for.

I didn’t know what I would choose when I walked into Waterstones on the West end of Princes Street. I had no category in mind. At school I had won a book voucher after excelling in history, and had set out to buy a history book only to be disappointed and resentful of the limitations this put on my choice.

Now, I allowed myself to choose anything. A cookbook or something explaining the chemical elements of the earth’s crust in layman’s terms even I could understand, were equally as valid as the novels. The biographies of people I had never heard of also held potential, more so than those of famous people I had heard of.

The miracle of my review running (and payment) happened to occur in the same week as Valentine’s day 2013. It is a fête I have always paid little interest in, regarding it with snotty and smug disdain as silly marketing since the age of twelve, when my mother finally stopped sending me Valentine’s cards. Yet it was the Valentine’s display which led me to the chocolate box purple book which would become one of my most valued possessions. ‘Gifts for Valentine’s day’ said the display, but I wanted to buy myself a gift, and I told myself – picking up the short story anthology and beginning to rifle through it – that one day I would share this gift with another.

It was a book of love stories, edited by Jeffrey Eugenides, author of The Virgin Suicides (one of the best love stories of all time if you like hazily beautiful, exquisitely messed-up and tantalisingly inconclusive in a way which simply works.) I took the book, and several others, over to a chair in the corner where I could read and make my choice hidden from view of the other shoppers and shelf-riflers. I don’t remember which other books I carried over to this lair , from which to make my choice. I feel I started My Mistress’s Sparrow is Dead before any other, but I may be wrong. I do know that it was Eugenides’ introduction that grabbed me.

On first glance I missed the apostrophe s after the word sparrow, reading the title as My Mistress Sparrow is Dead, and imagining a frail woman of Victorian beauty, mourned by her equally consumptive lover. The true title, and the story behind it, is why I love this book.

The Title, My Mistress’s Sparrow is Dead, he wrote, was taken from Roman poet Catullus who had written On the Death of a Pet Sparrow, a piece on the death of a bird belonging to his mistress Lesbia. Though in earlier poems he had lamented the love lavished on the sparrow as a detraction from himself, in the final people he concludes that it is better there was a sparrow, living or dead, than never any song. Eugenides wrote about how Catullus’ choice of words ‘passer pibiabit’ echoed the sound of a bird singing, trailing off as it did so.

Someone – I cannot source the quote now and it is making me crazy – once said that every great writer needs a broken heart somewhere in their past. I would contend that it is not only writers who need this, but humans. Without it, there’s something wonderful and terrible you have never experienced. Catullus’ quote is a more beautiful, less hackneyed way of saying that it is better to have loved and lost than never loved at all. When illustrated by a dead sparrow who once sang, the quote comes to life. The dead bird explains much.

Like most people, I have had my heart broken. ‘I went with half my life about my ways’ wrote AE Housman, on the aftermath of love.

My Mistress’s Sparrow is Dead led me to understand that lost love is - in spite of the name - not all about loss even though you feel like you have literally been torn in half (and no I am not misusing the word ‘literally’.)

Heartbreak is, to an artist, a gift - a gift most would choose not to receive, but nevertheless, a gift. To those who aren’t artists too, it changes you, carrying as you do elements of another person with you forever (a way of walking, a strange way the hair falls, the syllables they put the emphasis on when they speak.)

It was the introduction which spoke to me, which sent me to the counter to buy the book – the sole token of my fee which would survive time – but it was the stories in the book which stayed with me, from Faulkner’s breathtakingly twisted A Rose for Emily and Lorrie Moore’s clever first person guide on How to be An Other Woman. Chekhov’s The Lady with the Little Dog is also there, alongside a dreamlike story by Milan Kundera about a pair of lovers who get involved in a role play which neither has the power to stop. Both become different people unable to return to who they once were.

I wrote to Eugenides, finding his address online, telling him how much I loved the book and how I too wanted to write. I also told him the story of my broken heart, and said perhaps I would write that one day.

He wrote back saying my email had made his day. His reply made my year.